Tools and implements the raiers used in their work

INTRODUCTION:

The forestry comprised various successive stages, lead respectively by, picadors, tiradors and raiers. Of the three jobs the first one, very developed, is still live. The other two have disappeared.

Once the trees were on the ground, it was necessary to cut the branches and peel them; that work wasn't easy, and it was very tiring. Besides, it involved the extra risk of slipping the hatchet to the foot or the picador' leg.

When the trees were clean, they were cut with pre-established dimensions, according to several measures: trunks, "rolls" or beams in order to make the rais.

The estisorada was the kind of dam used by the raiers for picking up the barranquejada wood to enraiar-la (make the raft), when the flow of the river was already big enough to make it.

Here is an important document to help know the history of the fluvial transport of the wood from the Pyrenean forests: the guia. This document (guia) authorised the transport of a determinate number of pieces of wood classified according to specific dimensions, for a particular period of the year and through a determinate and concrete route.

The document makes reference to the different names that the pieces of

wood received depending on its size and of the entry to which they belonged

according to its place of origin.

We can also deduce that made the proposal on the part of the carpenter

employer, regarding the days of validity of the document, later this could

be modified by the provincial authorities according to the interpretations

or of the possibilities of use of the rivers.

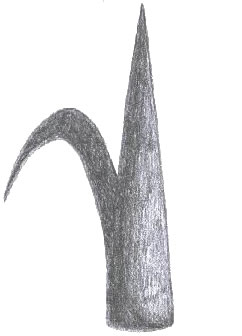

In all the above operations, the raiers used tools typical of their trade. Besides the ganxa to scroll the pieces, they used the "tribet" and the "cullera" to make the holes to nail the rowers, "l'estatge" or "llaçó" and the hatchet to condition the pieces to purpose and effect meet-them better, either to cut the "barrers", or to make the oars. This form of hatchet, which was used also by the picadors in the forest, was specially suitable to quadrejar the trunks even though it required force in the wrist and a special skill in its use.

The simplicity of all the technical process and the rational use of the

resources of the forest to fix every raft are, probably, the two more

curious characteristics of the process of assembling rais. Perhaps because

of this simplicity the photographers of the time didn't manage to leave

graphical evidence of these constructive details.

Once the stretches of each rais had arrived at the Ebre, wide and calm, many rais joined together in order to save labour hand since just two raiers could handle big amounts of wood.

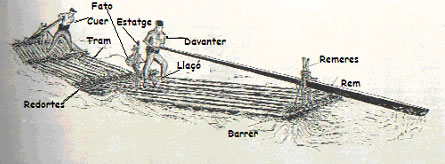

The parts of the raft are, among them the most important:

1. "Tram": Set of trunks, beams or pieces grouped one

on the side of the other.

2. "Barrer": thick bar of birch, that placed transversally

in the end of each stretch bears the interwoven of the "redortes".

3. "Estatge": was a pole similar to the ones described

above, placed behind the leading raier, forming a triple or fourfold fork,

and of which, therefore, the "fato" (the bundle of belongings)

and the rope could be hanged. In the river Segre, "l'estatge"

used to be ridden with two vertical poles and one of crossbar.

4. "Llaçó": Ring of birch, that is useful

to clamp the rem of the behind if it does not work.

5. "Rem": Beam of seven or eight meters, they cut with

axes, forming a wide shovel, and that it is useful to sending vessel as

if it were a rudder. (One in the stretch of the front and one in the stretch

of the behind).

6. "Remeres": were the place where the oars were tied

although they preserved the mobility for directing the rai. They were

made up of two poles, also of birch, nailed vertically to the logs, and

tied together with redortes. For facilitating the soft movement of the

oar, this was placed on a pillow of redortes as a kind of shock absorber.

7. "Tirants": "Redortes" used to clamp the

"remeres".

Next you can find a picture that shows the parts of a raft.

The way the travelled the rais in the river, not far away one from the others to help each other if that was the case, was called gathering voyage (viatge reunit).

By: Cristina Carrillo, Joan Escales, Silvia Servent and Jaume Garcia