| |

| |

|

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) es uno de los pensadores

más fecundos y universales del siglo XX: matemático,

lógico, autor polifacético, premio Nobel de

Literatura e influyente filósofo. Un pensador nada

convencional que recomendaba "no renunciar nunca a

mirar las cosas desde más de un punto de vista".

|

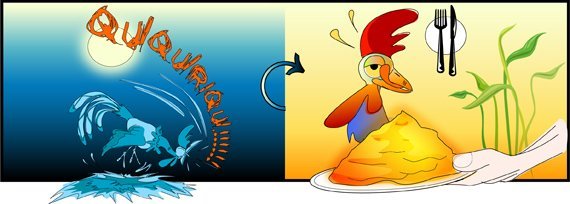

Siguiendo los pasos de su predecesor David Hume, cuestiona el

valor epistemológico del método inductivo. Los

procedimientos o métodos deductivos otorgan garantías

a las conclusiones obtenidas, es decir, lo que es válido

para todos, también lo es para una parte. Pero los procedimientos

o argumentaciones inductivas extraen conclusiones universales

a partir de datos u observaciones particulares, es decir, del válido

para una parte, más o menos representativa, se salta a válido

paral todo. Cuando argumentamos inductivamente, insinúa la

alegoría, ¿nos comportamos como los pollos?

|

|

| |

| |

|

It is obvious that if we asked why we believe

that the sun will rise tomorrow, we shall naturally answer,

"Because it always has risen every day." We have a firm belief

that it will rise in the future, because it has risen in the

past. If we are challenged as to why we believe that it will

continue to rise as heretofore, we may appeal to the laws of

motion. […]

Experience has shown us that,

hitherto, the frequent repetition of some uniform succession

or coexistence has been a cause of our expecting the

same succession or coexistence on the next occasion. Food that

has a certain appearance generally has a certain taste, and

it is a severe shock to our expectations when the familiar appearance

is found to be associated with an unusual taste. […] Experience has shown us that,

hitherto, the frequent repetition of some uniform succession

or coexistence has been a cause of our expecting the

same succession or coexistence on the next occasion. Food that

has a certain appearance generally has a certain taste, and

it is a severe shock to our expectations when the familiar appearance

is found to be associated with an unusual taste. […]

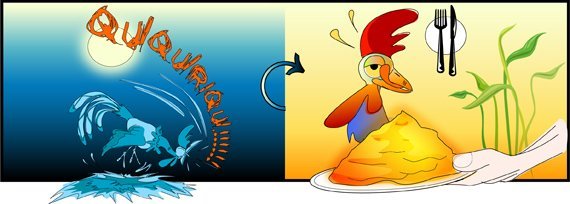

A horse which has been often driven along a certain road resists

the attempt to drive him in a different direction. Domestic

animals expect food when they see the person who usually feeds

them. We know that all these rather crude expectations of uniformity

are liable to be misleading. The man who has fed the chicken

every day throughout its life at last wrings its neck instead,

showing that more refined views as to the uniformity of nature

would have been useful to the chicken.

But in spite of the misleadingness of such expectations, they

nevertheless exist. The mere fact that something has happened

a certain number of times causes animals and men to expect that

it will happen aggain.Thus our instincts certainly cause us

to believe that the sun will rise tomorrow, but we may be in

no better a position than the chicken which unexpectedly has

its neck wrung. We have therefore to distinguish the fact that

past uniformities cause expectations as to the future,

from the question whether there is any reasonable ground for

giving weight to such expectations after the question of their

validity had been raised.

RUSSELL. Problems of Philosophy

|

|

| |

| |

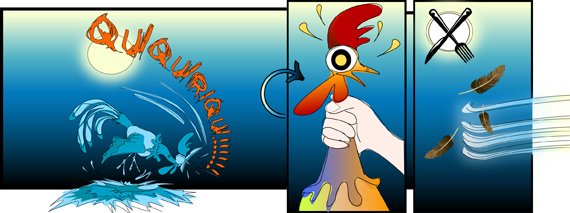

En nuestra vida cotidiana

todos hacemos uso de la inducción; los animales, también.

La inducción nos da seguridad psicológica;

pero no seguridad lógica. El pollo inductivista iba

incrementando su seguridad: cada vez que se le daba de comer, obtenía

una nueva confirmación de su convicción.

La inducción suele fundamentarse en la uniformidad o regularidad

de la naturaleza: la naturaleza no es caprichosa comportándose

ahora de una manera ahora de otra. Pero, ¿como se sostiene

esta uniformidad? Constatando que en el pasado o en un número

finito de casos ha sido uniforme o regular y que, por lo tanto (inducimos),

lo será siempre. Así, pues, se justifica el procedimiento

inductivo haciendo uso de un procedimiento inductivo; esta falacia

lógica se denomina petición de principio.

A pesar de todo, la inducción ayuda a adelantar en

nuestro conocimiento de la naturaleza. Las afirmaciones universales

que no podemos mantener inductivamente, las podemos proponer en

términos de probabilidad. Si habiendo observado diez

cisnes tenemos que abandonar nuestra afirmación "todos

los cisnes son blancos" puesto que hemos encontrado uno negro,

podemos afirmar que la probabilidad de que un futuro cisne sea blanco

es de 0,9.

|

|

| |

|

Experience has shown us that, hitherto, the frequent repetition of some uniform succession or coexistence has been a cause of our expecting the same succession or coexistence on the next occasion. Food that has a certain appearance generally has a certain taste, and it is a severe shock to our expectations when the familiar appearance is found to be associated with an unusual taste. […]